For the American philosopher John Dewey, art had an intimate connection with everyday life. Aesthetic experience could never be disentangled from our interactions with the common qualities of objects – from their colors, textures, shapes, lines, densities, and details. That is why in his book on aesthetics, Art as Experience, published in 1934, Dewey suggests that art is one experience among "different aspects and phases of a continuous interaction of self and environment." In other words, art is not alien to our perceptual relations with the ordinary things, images, and words that compose the social milieu we inhabit. Accordingly, he rejected the idea of art as something only for the elites – instead, art is inextricably linked with life, not something that sits outside or above it.

Later, in the 1960s, the turn to Conceptual Art emphasized the methods of decontextualizing and recontextualizing artifacts, imagery, and language. By dislocating these materials from their usual settings, artists aimed to reconfigure the ossified semiotic and instrumental values ascribed to them, performing both critiques of institutionalized art and a reframing of aesthetic judgment. In doing so, viewers had to rethink their own relations to the mundane: an object that only had utilitarian associations so far, now became strangely beautiful; an ordinary image that seemed to have no intrinsic visual charm on its own, now appeared as enchantingly odd; a word whose meaning seemed to be set in stone, now opened an endless process of reinterpretation. Such de/recontextualization of materials within new frameworks enabled an overall renewal of perception, as though we were looking at the world for the first time, as though we could see with fresh eyes, the aesthetic value that ironically hides in plain sight in the signs and things that surround us. Art came alive again.

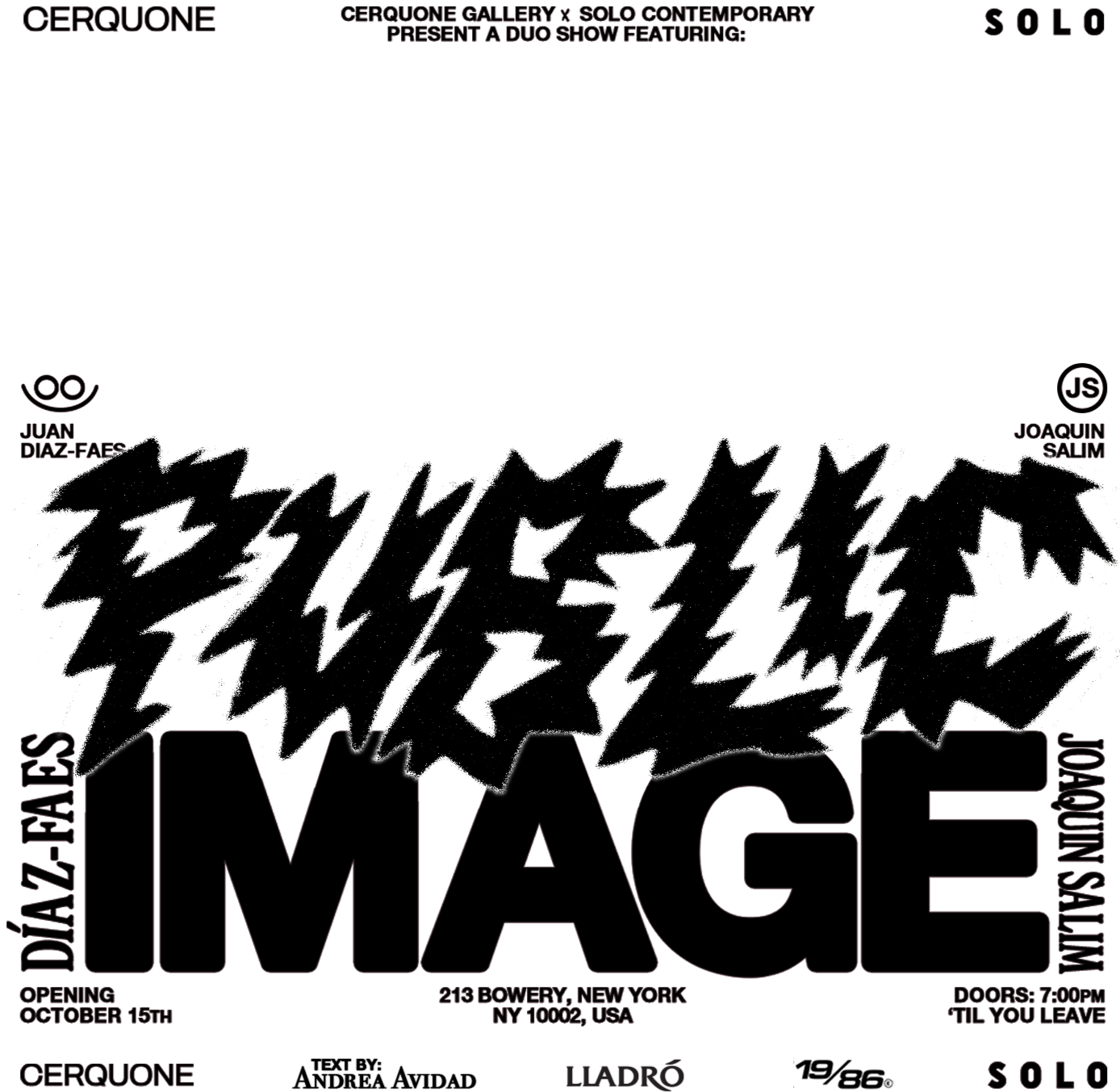

The duo exhibition by artists Juan Díaz-Faes and Joaquín Salim, brought to New York City by Cerquone Gallery under the title "Public Image," builds upon and even expands these ideas and traditions. Díaz-Faes defamiliarizes the conventional meaning associated with comics – as a graphic language that merely connotes entertainment – instead employing comics as a form of critique. Resorting to the conceptual figure of the mask, which repeatedly appears across his works as a circular black shape with a standardized and monotonous white smile, Díaz-Faes reflects on the social command to always be happy. Echoing the cultural theorist Slavoj Žiźek's critique of consumer society's structuring of desire as the ideological command to always "Enjoy!" ourselves, Díaz-Faes asks us to reflect on the weakening of the bonds between the individual and the collective. At the same time, however, these masks also serve as a psychological shield: perhaps indifferent individualism is a choice. Thus, his work articulates ethical questions for the viewer: How do we decide to live? With a responsible stance toward our shared realities? Or, with a smile that is not truly ours, but a product of solipsistic individualism?

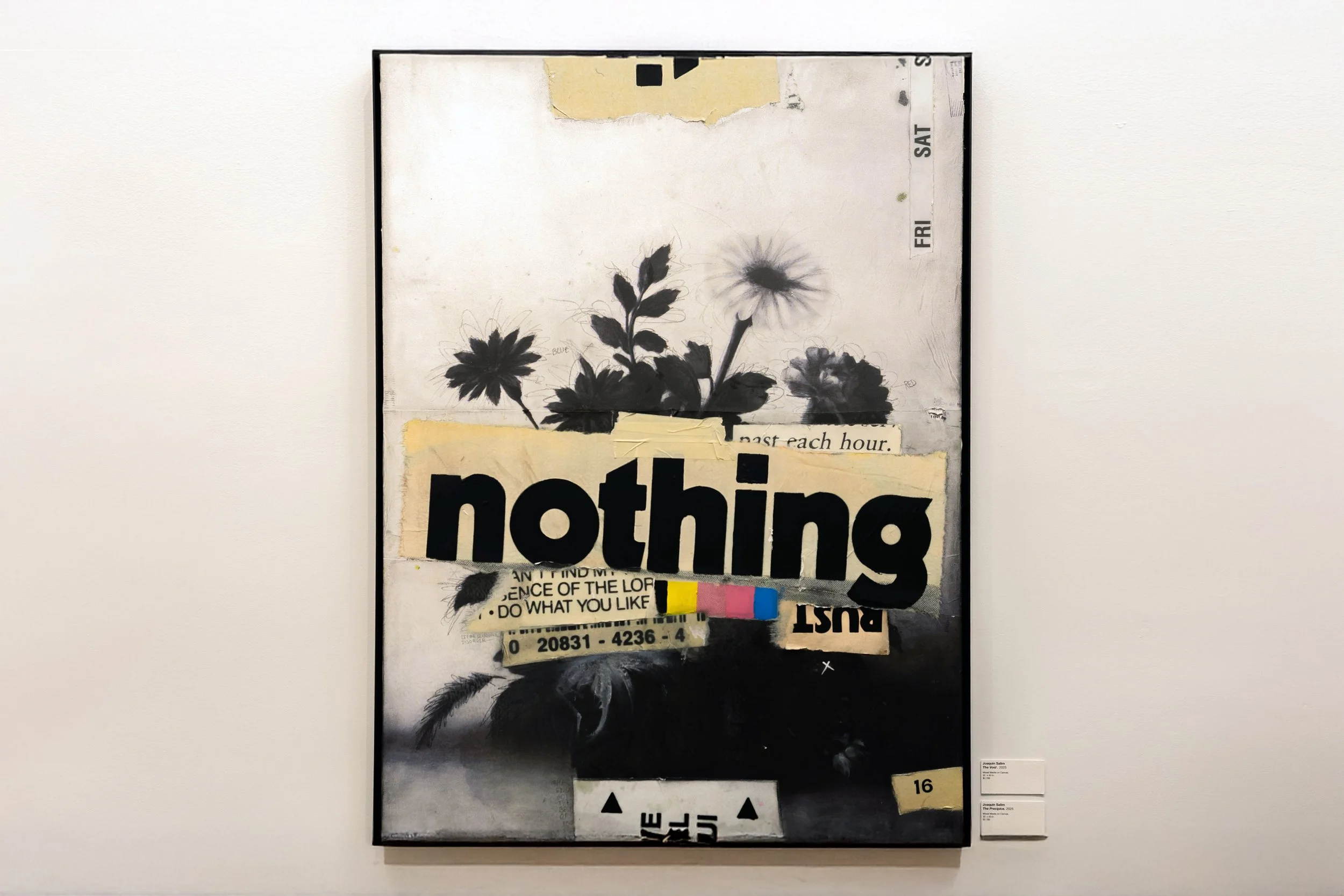

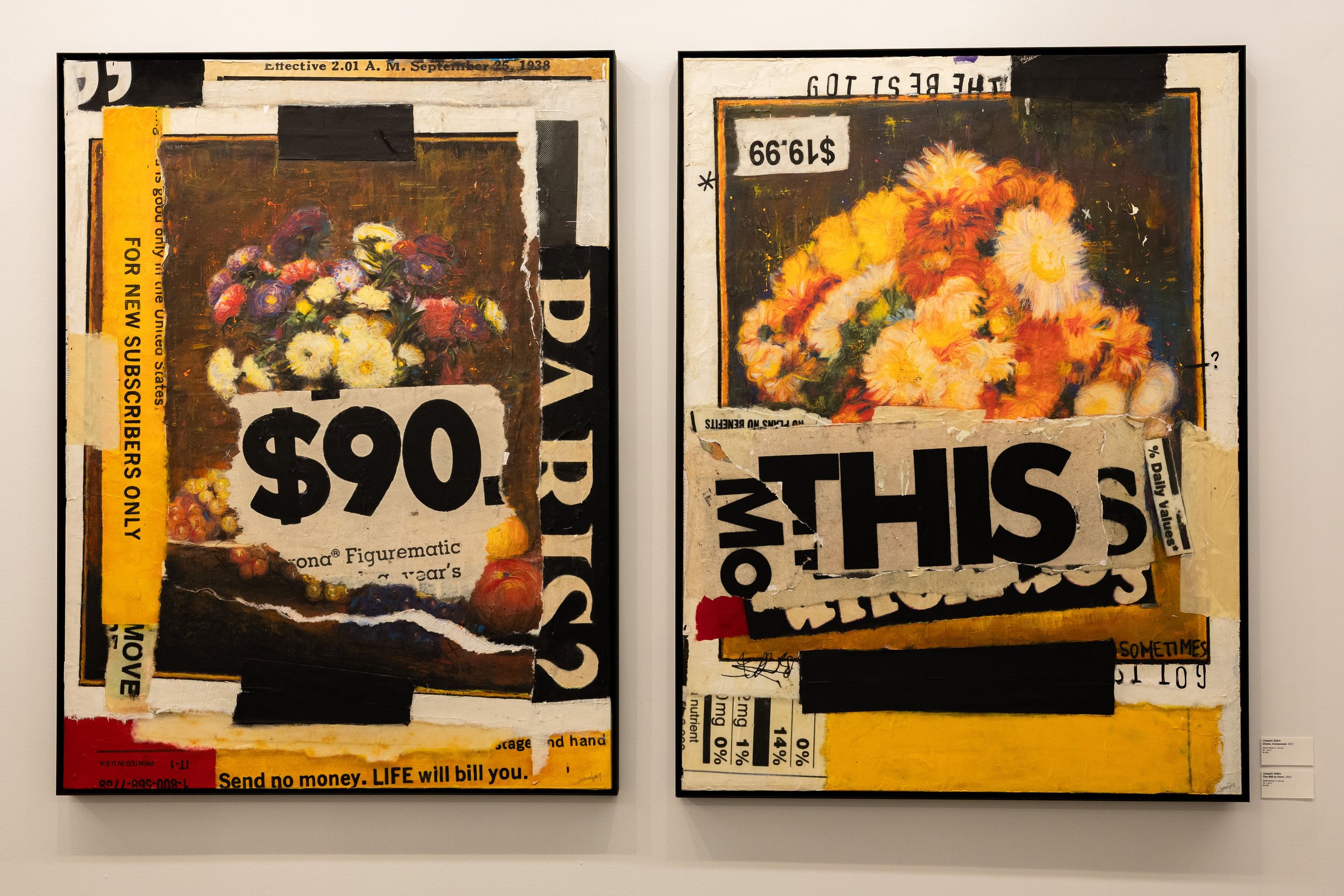

Joaquín Salim's prolific artistic practice employs techniques of deconstruction and reconstruction that metamorphose commercial language – a language of commodification and psychological conditioning – into poetic visual narratives. Working with found materials – a practice reminiscent of Marcel Duchamp's ready-mades and Kurt Schwitters's assemblages – Salim transforms mass media's prosaic semiotic codes into something new: familiar iconography acquires a novel status, requiring the viewer to reconsider the entrenched cultural weight carried by the signs and symbols we consume daily.

His work employs visual fragments that reference various temporal periods, spanning from the early 20th century to contemporary times, thereby reflecting on the evolution of an image and a word's own signification over time. Formally, Salim's aesthetics invoke a haptic visuality which synthesizes an experimental narrative through layers of heterogeneous components: the artist superimposes a cinematographic still with a price tag, a decontextualized piece of text, and a painterly brushstroke. In a single frame, eclectic laminations assemble compelling visual stories that reorient our sensibility toward the everyday things we unconsciously observe without really looking. Salim's artistic practice refocuses our experience of the multitude of visual and linguistic signs we encounter in our daily routines.

Together, these two artists' aesthetic praxes invite us to challenge our dull perceptual habits, to critically reassess our interactions with the codified image-based and language-based systems that bombard our day-to-day existence, and to examine our participation (or resistance) in the cultural status quo. But beyond critique, these works also tune our senses to the richness and possibility of meaning, to the sensory poetry that moves through and around us in the fabric of ordinary days, in life’s minor details, thus showing us that art is continuous with the dance of everyday life – as Dewey claimed almost one hundred years ago. The exhibition brings together a series of works that illuminate the polysemic role of the public image – an image whose, despite its encoded sense and function, becomes a vehicle for aesthetic freedom.

– Andrea Avidad